|

|

| Home Topics Memorials Miscellany Transcripts References Family History Glossary Latest Beeston Blog About us | Site Search |

|

The Lace Making Industry -

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year | Directory | Lace Makers | Frame Smiths |

| 1832 | Whites | 42 | 5 |

| 1835 | Pigots | 31 | * |

| 1854 | Wrights | 15 | 5 |

As we shall see, the number of those in Beeston in the lace trade, employers and employed combined, rose considerably over these two decades. In contrast to that, and although the directory sources are not numerous, the few we have seem to show a decline in the number of self-employed lace makers over this period. Some of these, know doubt, tried the lace trade for a short time and failed or simply moved on. Others may have become employees as the fewer businesses that remained consolidated and grew in size. The more successful individual entrepreneur lace maker tended to leave more trace, some of whom we have been able to put together to record their life as pioneers in the lace industry. Among these were :

Robert Thornhill - is known to have been operating three machines by 1829 48and was one of several small and medium sized lace makers known to have been operating on Villa Street about this time. Born in Beeston in 1786 49, he was active within the local Baptist chapel - as, it seems, were other lace makers in the Villa Street area. His workshops appear to have been at the lower end and east side of Villa Street, near to the Turnpike (High Road), It is this site, fronting also on the High Road, that was later acquired by William Thornhill 50, his only son by his first marriage to Ann Cox in 1806. Later, this was to become the site where William and two later generations of the Thornhill family traded as tailors (see more) for many years. Robert married twice more and had at least ten children with his third wife, Elizabeth Cockayne (previously Kerry), including four sons, each of whom worked as a lace maker at some time in their lives. By 1851, it seems that the business had been taken over by his son Richard who is then recorded as operating four machines, although his father is living in an adjacent property and was still described as a lace manufacturer 51. By 1861, Richard had begun to diversify away from lace making by taking the position of Assistant Overseer and Collector of the Poor Rate - although he is still recorded as a machine holder and employing one man and 2 boys 52. Robert died in 1863 53, by which time, it seems, lace making had ceased at this location.

Thomas Elliott - was one of several lace makers who were working in the Cross Street/Villa Street area by the 1830s. In 1829, William Booth had operated 10 machines there 54, and it appears to be his premises that were leased, in 1834 55, to Thomas Elliott who had recently moved, with his family, from Nottingham 56. Apparently built as a factory, this four storey building was known as Dobson's Mill or Bank Factory and was eventually to become part of the Pollard family's Swiss Mill (of which, more will follow). Elliott started at this site with just eight hand-operated machines but, in 1846, he introduced the 'Manchester' Jacquard to his Leavers lace machines 57. By 1851 he had expanded considerably, with 60 employees, and was also a small-scale farmer, then grazing 58 acres with the help of three labourers 58. Thomas had become a Wesleyan Methodist after his arrival in Beeston and was part of the group that broke away in 1849 to form a Wesleyan Reform Chapel which met, in its early days in a room at the nearby Commercial Inn but later built a chapel on Willoughby Street 59, probably with help from Thomas Elliott. By 1851, Elliott was the manager of the chapel farm which was then in the Cross Street area. After the death of his wife Mary in 1852, Thomas married a French widow, Marie Apolline Séraphine Gonard (née Lecerf). The couple moved to live in France, to the west of Vétheuil, Val d'Oise. Thomas died there in April 1868, aged 61. His widow continued to live there, at one point renting a house to Claude Monet, the painter. She died there in 1879, aged 72 60.

John Horsley - John and his brothers Samuel and James were perhaps more typical of the early small-scale lace making entrepreneurs as they appear to have appear to have survived adequately rather than prospered greatly in their business. They were apparently the sons of Samuel & Mary (née Young) Horsley and came to Beeston from Nottingham in the 1820s 61. It seems, however, that they avoided the severe difficulties that followed the period of 'twist net fever' that was then developing, as the first record we have appear in a 1832 directory which lists the firm of 'Horsley & Fawkes'. This is repeated in 1835 but, in 1840, John is listed trading alone as a lace maker in Beeston 62. In the census of the following year, each of the brothers is recorded as a Beeston lace maker 63 - as they still are in 1851, then all living very close together on Brown Lane, Beeston (now the upper part of Station Road), surrounded by a cluster of lace trade workers 64 and John had listed his business address in 1849 as Brown Lane 65. John died in 1852, followed by Samuel in the years before 1861 and James in 1862, after first moving to Chilwell 66.

Henry Cross - was part of a large, complex and long standing local family. Two men of that name, father (1782-1842 67) and son (1801-1873 68), were making lace at various times during this early period and it is sometimes unclear which is referred to in the available records. Henry senior is particularly interesting because it appears to be he who is recorded as a signatory of the Restriction of Hours Deed in 1829 as the owner of six lace machines - the fourth largest of the Beeston owners who signed. It appears that he and his son were working these machines in the Villa Street area, probably adjacent to where William Booth was operating ten machines. As we have seen, a new street was opened up at that time, joining Butchers Lane (now Wollaton Road) and Villa Street in the area where Booth and Cross were operating. This is Cross Street, in all probability named for Henry Cross. Although, father and son continued to make lace in the decade following the collapse of trade at the end of the 1820s, it seems this was on an increasingly reduced scale and, eventually, both were to move away from Villa Street and leave the lace trade. By the time of his death in 1842, Henry senior had began to work as a baker, a trade that he was following in 1839, when his daughter Millicent (c1812-1881) married John Frettingham, a son of George Frettingham the local market gardener 69. In 1843, another daughter, Rebecca Cross (c1818-1885), married John Frettingham's brother Henry 70. The Frettingham and Cross families were long time members of the local Baptist community, whose chapel was erected on land adjacent to the Frettingham nursery gardens on Moore Gate. By 1841, it appears that Henry junior had moved briefly to Leicester 71 but returned following the death of his wife. In 1851 he was still working as a lace maker 72 but it appears then that he, along with his mother and brother Samuel, he later lived and worked in association with the Frettingham family and ceased to be associated with the lace trade. By 1861 73 he was earning is living as a flower seller and his brother (who had previously worked as a 'lace agent') was working as a gardener, presumably with the Frettinghams. It seems that the experiences of this family, amply demonstrate the effect of the boom and bust years experienced in the lace trade in the 1820s.

James Cross - was born in 1784, the son of James and Sarah (née Whitehead), and was the cousin of Henry Cross senior, whose life as a lace maker is outlined above 74. James worked as a blacksmith and, it seems, was one of many with these skills who turned his hand to making lace machines during the boom years of the 1820s and it is therefore very likely that he was the source of Henry's six machines. James was still working as a blacksmith up to his death in 1846 and appears to have been largely unscathed by the fallout of the turmoil in the lace trade. His eldest son Samuel (1808-1888) 75, who had worked with his father as a blacksmith, had turned his attention entirely to building lace machines by 1861 76 and continued to do so until his death, albeit in nearby Long Eaton 77, where the lace trade was also expanding greatly. James' daughter, Mary Ann Cross (b. 1816) married Thomas Thornhill 78, a lace maker and son of Robert Thornhill whose involvement in the early lace trade is outlined above. Samuel's son James (1831-1872) continued to work alongside his father in Long Eaton before his early death there, aged 41 79. In turn, at least two of his sons continued in the trade.

These were just a few amongst many pioneers in these early days of the lace making in Beeston up to 1850, a period during which the trade had developed and begun to mature to become a major part of the industry in the Nottingham area. Eventually, as we shall see, it was to grow much further, even to compete directly in world-wide markets, but, it is now appropriate to demonstrate - using the census returns for 1841 (despite its limitations 80 ) and 1851 - just how important lace making had already become to the local economy.

| Census | Population | Lace making | % of | Working Household Heads | |||

| Year | Total | Working | Workers | Workers | Total | Lace | % of all |

| 1841 | 2790 | 989 | 180 | 18.2 | 508 | 123 | 24.2 |

| 1851 | 3016 | 1729 | 426 | 24.6 | 572 | 141 | 24.6 |

| Change | 226 | 740 | 246 | . | 64 | 18 | . |

| % Change | 8.1 | 74.8 | 136.7 | . | 12.6 | 14.6 | . |

It is clear from this table that, by 1851, about a quarter of Beeston's working population and a similar proportion of households, derived their income from the industry - albeit with with some imbalances, since those working in the industry were disproportionately male, a trend that was to continue with lace machines operated almost exclusively by men, while women worked on ancillary operation, such as winding and mending. In 1851, only 128 (30.0%) of the lace makers in the working population were female. Females working in all other occupations numbered 606 which was 46.5% of the total. Only 25 females were recorded as working in the lace trade in 1841, although this is probably distorted by the under-recording of occupations of those who were not the head of a household.

Twenty Years of Decline - The stablisation and tentative growth in the lace industry following the crisis of 1829 was, as we have seen, certainly evident in Beeston and this had played its part in the increase in population numbers. However, this was not to last. After 1851, the effect of mechanisation of lace machines began to bite, as smaller operators found difficulty in responding and competing. This was a change that Nottingham itself was able to respond to more ably and much more of the activity in the trade began to be transferred there. Despite his commitment to mechanisation, as we have seen, Felkin's Beeston business failed in 1864 with the loss of close to 100 working machines and the employment that went with them. The other mechanised Beeston factory - Kirklands - continued throughout this period, now under the control of Henry's son, William Kirkland but, again as we have seen, on a steadily diminishing scale. Smaller operators - often working just one or two machines, were hit badly and many became discouraged during this time - with the notable exception of Thomas Pollard and his energetic son, John who continued, for the time being on a small scale, in the Villa Street, Cross Street area of Beeston and, as we shall see, survived to later become major players in the trade.

Faced with this decline in the lace trade - and in other local industries too - the economy in Beeston became stagnant, if not in decline, for about twenty years. This can be amply demonstrated by reference to the census statistics for 1861 and 1871 when compared to similar figures for 1851 :

| Census | Population | Lace making | % of | Working Household Heads | |||

| Year | Total | Working | Workers | Workers | Total | Lace | % of all |

| 1851 | 3016 | 1729 | 426 | 24.6 | 572 | 141 | 24.6 |

| 1861 | 3191 | 1658 | 413 | 24.9 | 664 | 175 | 26.3 |

| 1871 | 3135 | 1587 | 264 | 16.6 | 673 | 124 | 18.4 |

| Change 1851-71 | 119 | -142 | -162 | . | 101 | -17 | . |

| % Change | 3.9 | -8.2 | -38.0 | . | 17.6 | -12.1 | . |

This table, showing aspects of the population of Beeston and the number of lace makers over this period, demonstrates clearly largely stagnant population growth - only 3.9% - with a 38% drop in the number of lacemakers clearly making a substantial contribution to the overall standstill. Interestingly, however, the number of working heads of household increased more markedly (up 17.6%) - that is, relatively more families were forming - which points to a population that is consolidating and aging. Alongside this, the number of these heads - that is, the main family earners, usually male - working in the lace trade saw only a small numeric decline, perhaps indicating the relative survival of a core of skilled, better quality, traditionally male jobs in the industry. Alongside this, the number of female workers in the lace trade - traditionally working in support roles to the male lace makers - saw a disproportinate decrease in Beeston - down 43% between 1851 to 1871.

The lace making trade - and therefore Beeston - was clearly drifting. However, happily, two entreprenours with other ideas were soon to emerge and were to change things dramatically and, together with other initiatives, were to transform Beeston's economy almost overnight.

Booming Again ! - during the early 1870s there were signs of new opportunities in the market for lace, notably in America. Obviously, those firms operating out of the Nottingham's Lace Market were well placed to exploit these opportunities using the traditional practices within the industry of acting as facilitators for finishing and marketing lace produced by a myriad of smaller makers. In Beeston, one man saw his opportunity to exploit these markets and, in the process, to bypass the Nottingham monopoly by creating a lace business that did all those things under one roof. That man was Frank Wilkinson. At more or less the same time, John Pollard, the enterprising son of Thomas Pollard, also saw opportunities within the trade. Working in the same era, but in separate sectors of the lace trade, they were to rejuvenate the lace industry in Beeston and, along with other business sectors, help more than double Beeston's population over the twenty years up to 1891 and revive its economy in the process. These dramatic changes in the size and shape of Beeston's economy that are seen clearly in the 1881 and 1891 figures included in this summary:

| Census | Population | Lace making | % of | Working Household Heads | |||

| Year | Total | Working | Workers | Workers | Total | Lace | % of all |

| 1871 | 3135 | 1587 | 264 | 16.6 | 673 | 124 | 18.4 |

| 1881 | 4479 | 2115 | 423 | 20.0 | 877 | 151 | 17.2 |

| 1891 | 6945 | 2950 | 803 | 27.9 | 1258 | 252 | 20.0 |

| Change 1871-91 | 3810 | 1363 | 539 | . | 585 | 128 | . |

| % Change | 121.5 | 85.9 | 204.2 | . | 86.9 | 103.2 | . |

While, as the more detailed figures show, this growth arose from various factors, it is the lace industry that concerns us here - and the figures were very significant. By 1891 the numbers employed in the industry had almost doubled since the previous high in 1851 and had more than tripled since the low point of 1871. By 1891, over 27% of the working population were employed in the lace trade, including a significant increase in the involvement of women and girls. The lace trade had become hugely important to Beeston's economy and it is time to look at the individuals that led this turnaround.

John Pollard - the story of the Pollard family and its contribution to the lace making industry in Beeston has been told comprehensively by Ernest Pollard in his book, 'Pollards of Beeston - a Century of Lace Making'. As this book also

appears on this site here, it is not necessary to retell the story - other than to put it in the context of our narrative. This story of enterprise, involving four generations of the Pollard family,

arose from very humble origins during the pre-1851 era when, as we have seen, the trade was carried out, in the main, by individual lace makers or small groups working together and who were only tentatively beginning to move to a factory environment

and mechanisation. While it was Thomas Pollard (1803-1880) that put in place the foundation of this family enterprise in that early era, it was his son, John Pollard. who took the business to the success story that it became. Significantly,

this change coincided with the two decades of particularly significant growth that we have identified. It was a change that formed the basis of a major enterprise that was to continue through the next two generations until the decline of the trade generally saw its eventual

closure.

John Pollard - the story of the Pollard family and its contribution to the lace making industry in Beeston has been told comprehensively by Ernest Pollard in his book, 'Pollards of Beeston - a Century of Lace Making'. As this book also

appears on this site here, it is not necessary to retell the story - other than to put it in the context of our narrative. This story of enterprise, involving four generations of the Pollard family,

arose from very humble origins during the pre-1851 era when, as we have seen, the trade was carried out, in the main, by individual lace makers or small groups working together and who were only tentatively beginning to move to a factory environment

and mechanisation. While it was Thomas Pollard (1803-1880) that put in place the foundation of this family enterprise in that early era, it was his son, John Pollard. who took the business to the success story that it became. Significantly,

this change coincided with the two decades of particularly significant growth that we have identified. It was a change that formed the basis of a major enterprise that was to continue through the next two generations until the decline of the trade generally saw its eventual

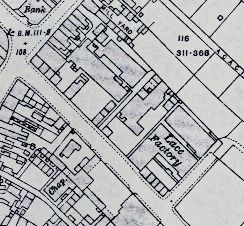

closure.John Pollard was born in Beeston in 1838 and received only the limited education then generally available. By the age of twelve he was already working and, over the next 20 years, gained a thorough knowledge of the lace trade within the family. By the 1870s, he was in a position to take the initiative and use his undoubted talent as entrepreneur to take the family business to a completely new level. First he rented, and soon acquired, existing factory buildings - including Dobson's Mill - in the Cross Street area of Beeston and was eventually to put together the various factory buildings bounded by Cross Street, what is now Wollaton Road and Villa Street, to form the complex known as Swiss Mills. The basis if this enterprise was the family's own lace making business, now working in a factory environment and, from then on at least, exclusively as makers of Leavers Lace at the quality end of the market. In contrast to other local factory enterprises that we will discuss, the firm concentrated its efforts almost entirely on design and manufacture and never involved itself in the 'finishing' processes. And too, its lace was usually marketed through merchants in Nottingham's Lace Market, often for export to America and Europe. This well defined formula demonstrates that Pollard was clear about his position in the now much more mature market for lace and was prepared to concentrate on it. It was a policy that served him well while, at the same time, providing employment for the most skilled in the lace trade. By 1881, his total workforce was only about 32, of which probably about half were highly skilled 'twisthands' or designers but, in its heyday later in its history, the workforce was to grow to about 120 including, in the early 1900s, twenty working in the company's drawing office - a key element in the success of a Leavers lace business. With the closure of Kirkland's factory around 1885, the company had become the principle Leavers lace making factory in Beeston,

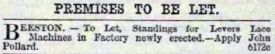

However, although it remained his primary activity, he did not confine himself solely to making lace. He was also, of course, well aware that much of the remainder of the trade was carried out in the traditional way, by lace makers working on their own or in very small groups but, increasingly, they lacked the space required for increasingly large machines and flexibility in their existing work areas - often still associated with residential buildings. He therefore set out to cater for - and, of course, profit from - this need, by renting individual machine spaces

- known as 'standings' - with access to steam power, within his factory complex. He already had a few tenants in his existing buildings when, between 1884 and 1886 he built a large new factory building in the remaining space of the complex,

specifically for the purpose of renting space to others in the trade. It was successful from the start, essentially consolidating and bringing together many of the smaller operators - although each would have carefully guarded their individual business secrets. His

advertisement (shown here from September 1886), which appeared in the local paper for several months, appears to have had good results and the building was soon well utilised. By 1887 he already had 21 tenants, almost all of them in the lace trade, and there were many others to follow.

- known as 'standings' - with access to steam power, within his factory complex. He already had a few tenants in his existing buildings when, between 1884 and 1886 he built a large new factory building in the remaining space of the complex,

specifically for the purpose of renting space to others in the trade. It was successful from the start, essentially consolidating and bringing together many of the smaller operators - although each would have carefully guarded their individual business secrets. His

advertisement (shown here from September 1886), which appeared in the local paper for several months, appears to have had good results and the building was soon well utilised. By 1887 he already had 21 tenants, almost all of them in the lace trade, and there were many others to follow. The building itself stood prominently on Wollaton Road, with the name "Swiss Mills" and John's initials and the year ("18JP86") showing just below the gable at that end. It can be seen on the right in the picture (shown left), the tallest in the complex. What was Dobson's Mill is

glimpsed on the left of the picture. The main Swiss Mill building, in particular, remained a familiar landmark in Beeston for almost 100 years until it was destroyed in a spectacular fire in 1984.

The building itself stood prominently on Wollaton Road, with the name "Swiss Mills" and John's initials and the year ("18JP86") showing just below the gable at that end. It can be seen on the right in the picture (shown left), the tallest in the complex. What was Dobson's Mill is

glimpsed on the left of the picture. The main Swiss Mill building, in particular, remained a familiar landmark in Beeston for almost 100 years until it was destroyed in a spectacular fire in 1984.In his lifetime, John Pollard built and moved his family to Cromwell House, a then fashionable home with formal gardens, away from the factory, the north of what is now Abbey Road and beyond the end of what is now Cyprus Avenue. By the time of his death in July 1903, he had made a considerable fortune - over £25,000, which would have the purchasing power of over £6million today. This had been achieved by demonstrating excellence in his firm's lace and the foresight to provide for the needs of the wider lace making trade. He had also trained his surviving son, Arthur James Pollard, to continue to manage the business as part of a trust which continued until John's wife's death in 1922 - a story that we will include later in the context of that later era.

Nevilles Factory - the Leavers lace maker, William Neville (1847-1926 81), the son of William Neville, a lace agent, and Mary Ann, his wife, had moved from Basford to Beeston and started in business as a Pollard tenant in the

Bank Factory by 1871, employing nine men 82. During the following decade, he was joined by his brother, Charles Neville(1849-1918 83) and, in 1880, they built a new lace factory,

just beyond the Chilwell boundary, butting up to the south side of High Road, Chilwell and alongside Factory Lane. This substantial building was 40ft wide with four storeys, each with ten 8ft 4in wide standings and topped by a 30ft lantern roof, forming a room that was used for bobbin winding and similar operations

84. By 1881, they were employing 41 men and 17 females, between there and their Beeston factory 85. In 1886, they extended their factory by adding a wing at a right-angle to the

original, inside the Beeston boundary, on the south side of Chilwell Road, Beeston, on the corner of Wilmot Lane. This building housed five standings, each 8ft 6in wide, on each of the four storeys, also with a lantern roof. The two buildings together formed an L-shaped - as can be seen in the picture, shown

right - joined along the Beeston/Chilwell boundary.

Nevilles Factory - the Leavers lace maker, William Neville (1847-1926 81), the son of William Neville, a lace agent, and Mary Ann, his wife, had moved from Basford to Beeston and started in business as a Pollard tenant in the

Bank Factory by 1871, employing nine men 82. During the following decade, he was joined by his brother, Charles Neville(1849-1918 83) and, in 1880, they built a new lace factory,

just beyond the Chilwell boundary, butting up to the south side of High Road, Chilwell and alongside Factory Lane. This substantial building was 40ft wide with four storeys, each with ten 8ft 4in wide standings and topped by a 30ft lantern roof, forming a room that was used for bobbin winding and similar operations

84. By 1881, they were employing 41 men and 17 females, between there and their Beeston factory 85. In 1886, they extended their factory by adding a wing at a right-angle to the

original, inside the Beeston boundary, on the south side of Chilwell Road, Beeston, on the corner of Wilmot Lane. This building housed five standings, each 8ft 6in wide, on each of the four storeys, also with a lantern roof. The two buildings together formed an L-shaped - as can be seen in the picture, shown

right - joined along the Beeston/Chilwell boundary.A building of this size was clearly intended to attract lace maker tenants as well as to house the Nevilles' growing lace making operation. Interestingly, it was a contemporary and direct competitor of Pollards' Swiss Mill and it is clear that the demand was there as, by 1894, at least eleven lace making tenants were operating there 86 and some were occupying converted cottages on Wilmot Lane for drafting and designing. In 1906, the complex was further extended by adding a single-storey building, 45ft wide, housing seven 9ft 6in bays, behind the original building and alongside Factory Lane. This is believed to have been built for Arthur Metheringham, one of the Nevilles' lace making tenants.

The Nevilles had an interesting family connection with the famous economist John Maynard Keynes which is described in some detail here. Although that story was complicated by the family's then dedication to Congregationalism, both William and Charles Neville were active Baptists and thus part of a tradition of lace entrepreneurs within the Beeston Baptist community. Both became Trustees of the Beeston chapel in 1885 and remained so until their respective deaths. William was a contributor, along with Benjamin Venn and Charles Pearson, when Venn Hall was built, as an adjunct to the Union Chapel on Dovecote Lane, Beeston in about 1888 87.

The Neville brothers had settled in adjacent houses on Park Road, Chilwell, long before their respective deaths, Charles in 1918, followed by William in 1926. After this, it seems the buildings, appear to have been managed by Charles' son Ralph who continued to live in the family home, both before and after his marriage to Gladys Evelyn Clarke in 1932 88. During this period, the factory continued to be occupied by lace trade tenants though probably, as in Beeston, with an increasing number of other trades coming in as the lace trade faced increasing difficulties in the inter-war period. One such early tenant was the tool maker, Johnson Brothers, who were operating from the factory by 1922 and, in 1934, the firm that was to eventually to take over the whole factory, started up in the lantern space. This was the well known lathe manufacturers, Myford Engineering Limited founded by Cecil Moore (1889-1977 89), who had himself worked as a lace maker in his earlier years. Eventually, by the 1950s, this firm had become the sole occupier and the building became widely known as 'Myford's Factory'. This move towards engineering use may well have been inspired by Ralph Neville. Although Ralph had trained as a lace draughtsman, he developed a life-long interest in engineering, especially after serving, as a 2nd Lieutenant with the Notts & Derby Regiment. In March 1918, he was discharged after suffering shell shock and spent over a year convalescing, during which time his father died and after which, it seems, he did not return to the lace trade 90. There is an excellent account of Ralph's interest in engineering and an insight into aspects of Nevilles Factory in Jack Martin's memories which can be seen here.

The Wilkinson Family - originated from Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire where three generations had worked as framework knitters. In Beeston terms, the best known of the youngest generation was Francis (Frank) Wilkinson, a remarkable man, a brilliant entrepreneur, who played a major part in transforming Beeston's economy in the latter decades of the 19th century - and shaking up the lace trade in the process.

In some ways, his background was similar to that of John Pollard as he too was able to develop skills first acquired by his father and, in his case, his grandfather. Francis was born in Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire in 1844, the youngest of five children born to Michael & Elizabeth (née Harrison) Wilkinson. Both Michael Wilkinson (1809-1880) and his father, George Wilkinson (1784-1855 91) were framework knitters at a time when the trade generally, not least in Hucknall where they lived, was badly in decline. George, who had moved to Hucknall from Melbourne, Derbyshire, along with, it seems, a number of prominent knitters, had done better than most and, by 1841, he had about 60 knitters working for him - though, by that time, the trade generally was particularly badly hit.

Michael Wilkinson, with a wife and family of five to support, appears to have made every effort, and with some success, to rise above the poverty which had permeated the hosiery knitting trade 92. In the late 1840s he tried moving to Radford, then expanding into its suburb Hyson Green, where he may have found more steady work. In 1852, however, there had been a significant change in prospects in Hucknall when a group of experienced knitters, including Michael, had been able to modify their frames to produce knitted falls in wool in the style of Shetland shawls, a product that offered a new life to the trade. Michael moved back to Hucknall where, for almost twenty years he and his two eldest sons were able to prosper in this new line of business.

During these years, Francis Wilkinson, had set out to develop a career of his own 93. After a short time as a grocer's assistant in Nottingham, he found work - and vital experience - in the fast-growing lace trade in Nottingham. Eager to branch out on his own, he found an opportunity in what was then known as 'New Chilwell', an area adjacent to, and just beyond the Beeston boundary. There, in 1870, he was able to acquire the remains of a building known as 'Chambers Factory' where the lace maker James Chambers had operated a few machines as early as 1844, but was now abandoned and derelict following a fire. Over the next 25 years, the site, clustered around the Chequers Inn and taking in Wilmot Lane, Middle Lane and Factory Lane, would be developed greatly, to form Hall Croft Works. At first, the firm concentrated on the still fashionable knitted shawl trade and Michael moved to Chilwell to oversee production and an increasing number of knitters left Hucknall to join him there - a trend that was to continue as the business grew.

By this time, Francis - usually known as 'Frank', a name we will use - had himself moved to Middle Lane, Chilwell although, at this stage his personal life appears to have been somewhat behind his fast-moving business life as his marriage to Elizabeth Brett Stephenson 94, with whom he was living, and with their two children, at the time of the 1871 Census 95, did not take place until towards the end of 1872, around the time of the birth of their third child 96.

Very soon, other members of Michael Wilkinson's family were to become involved, directly or indirectly, in Frank's enterprise which, as we will see, soon extended to a major operation in Beeston and another in Draycott, in Derbyshire. Michael himself, died in 1880 but by that time the Chilwell factory was in full swing as a knitted shawl factory serving markets both home and abroad and a factory at Beeston was also under way, mainly making lace curtains, also for international markets. By then, almost all of Francis' siblings, the sons and daughters of Michael and Elizabeth Wilkinson, had taken their respective place in this major undertaking:

Charlotte Wilkinson - their eldest child, was born in Hucknall in 1832. In 1855 she married John Joseph James, a Radford lace maker. By 1891, he was working as a lace curtain maker at the Draycott factory. Each of their sons, Charles (b. 1856) and George (b. 1858), worked as lace curtain makers at the Beeston factory. George was living with, and apprenticed to, Francis and Elizabeth at the time of the 1871 census 95, did not take place until towards the end of 1872, around the time of the birth of their third child 97.Not all of Frank Wilkinsonís group of senior employees were family. Given that he had the same surname, it is usually assumed that Walter Wilkinson, who developed the market for the firmís products in America, was related to Francis and they have sometimes been described as brothers. In fact, this was not the case. Walter was born in 1851 in High Hoyland, Yorkshire, the son of farmer John Wilkinson and Sarah his first wife and, perhaps remarkably, there appears to be no family relationship of any kind. However, both men became key to the success of the business from its early days up until Walter's untimely death in 1893. The story of Walter and his remarkable wife Emily deserves to be told it its own right and will be included in its natural place in the narrative.

Hannah Wilkinson - their second child, born in Hucknall in 1834, was the exception in that she does not appear to have become associated with Francis's enterprises. After 1861, when she was living in Radford, she has not been traced.

Samuel Wilkinson - was their eldest son. He was born in Hucknall in 1836 and learnt to knit on the frame as an apprentice to his grandfather, afterwards working as a knitter in Hucknall and was one of those who converted to knitting shawls. By 1871 he had nine employees working in Watnall Lane, Hucknall, By 1881 however, he had joined the Chilwell operation as foreman of the woollen shawl factory. He died in 1889 leaving only £15. He and his wife Sarah (née Marriott) had at least 11 children including four sons, each of whom worked in the lace trade. Two of them, Charles and Ernest, left for America to work at the lace factory in Zion City (which will be discussed fully later).

George Wilkinson - their second son, born in Hucknall in 1841, started his working life in much the same way as his older brother. Like him, he was manufacturing shawls in Hucknall with 11 employees, by 1871. By 1881 he had moved to Beeston but, in contrast to others in the family, involved himself in business opportunities which arose indirectly from the success of the Wilkinson enterprise in Beeston. Eventually, as we will see, of all of the brothers, he was to achieve the greatest long-term financial success. A first, he kept the Durham Ox public house on Beeston's High Road but also began to build houses for the growing workforce in Beeston, including the rows of terraced housing that remain a feature today around the centre of Beeston, such as those on Commercial Avenue, Wilkinson Avenue, Derby Street and City Road. He also served as a Councilor on the then Beeston Urban District Council.

This detachment from the mainstream of the family business while, at the same time, being in a position to benefit from the growth in the local economy that it had helped to generate, served George well. This independence placed him in a key position when his brother Francis was clearly financially stretched in the 1890s, it was he that took charge after his brother's death in 1897 and, when it was clear that the business would not be viable without his brother's driving personality, he ensured the relatively orderly closure of the business. This part of the story will follow in its natural position in the narrative.

Anglo-Scotian Mills - In about 1874, Frank Wilkinson made his next move when he acquired the factory site in Beeston, north of the village centre on what is now the corner of Wollaton Road & Albion Street, where the Felkin family had previously operated. It was a move that was to change Beeston dramatically and to provide more that twenty years of employment and prosperity - but not without some dramatic setbacks, as we shall see.

Up to that time, almost all lace firms in the Nottingham area, big and small, confined themselves to their own part of the overall production and marketing processes. Those firms that made the lace would often pass on their product to specialist firms for finishing and marketing would be handled by specialist merchants and agents. Increasingly, by the time we are now considering, marketing involved the development and management of export markets. By this date too, the Lace Market in Nottingham was the centre for most of the merchanting functions, taking product from lace producers and finishers around the region. Although there were, of course, some firms that carried out several parts of these processes, this was not the general rule with many content to concentrate on their own expertise and benefited from the relatively smooth cash flow resulting from middle men taking their product.

Frank Wilkinson was not, however, content with that type of structure and was determined to set up an organisation which would integrate all processes - from designing to marketing - under one roof. And, his ambition was even more daring. Not content with one line of product he took on more - first adding lace curtains to the shetland shawls that he had produced successfully at Chilwell - and eventually on three sites - and then adding hosiery manufacture, all part of the integrated organisation. It took a dedicated and driven person to create such an organisation and to make it an undoubted success and Frank Wilkinson was to prove that he was that person. His success was to prove hugely beneficial to Beeston as it entered a period of growing maturity as a town.

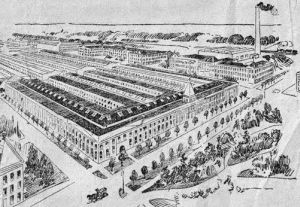

An enterprise such as this needed considerable factory space and Frank immediately set about enlarging the small abandoned factory on the site, first adding about 70 feet at the back and later an extension to the front with 300 feet facing onto Wollaton Road. Still later he added a further wing, 120 feet long, running towards The Poplars on the north side. By 1885, when a further substantial unit was added at the rear of the site, the complex extended over two acres and production was at its height. The machines, 60 curtain lace machines, 45 warp machines and 70 shawl frames, operating on two shifts, were positioned throughout the ground floor. Winding and finishing took place on the next floor while, above that, a warehouse held large stocks of finished goods destined for both the domestic and overseas markets, while lace dressing - transforming the raw lace to a marketable product - took place in the upper storey under a lantern roof. Also within this comprehensive manufacturing complex were design offices, seeking constantly to produce the patterns that would keep ahead of the competition and attract a demanding market. Of course, too, an organisation of this size also needed a strong management structure and administration - needs not always appreciated by strong personalities, such as Wilkinson, who had grown a business from small beginnings. It seems though that the business that Wilkinson had created had all the right ingredients for success not least of which were his own undoubted energy and entrepreneurial skills. Indeed, his personal energy and dedication were legendry with no aspect of the business escaping his attention and personal involvement. He himself took responsibility for developing sales to the home market and, when he was injured in a railway accident, he continued to travel the country on crutches. He applied his inventive mind to developing and improving the buildings and the machinery and processes that were used in them. And, whenever he was in Beeston, no day was complete without his personal supervision of the packages leaving the railway station.

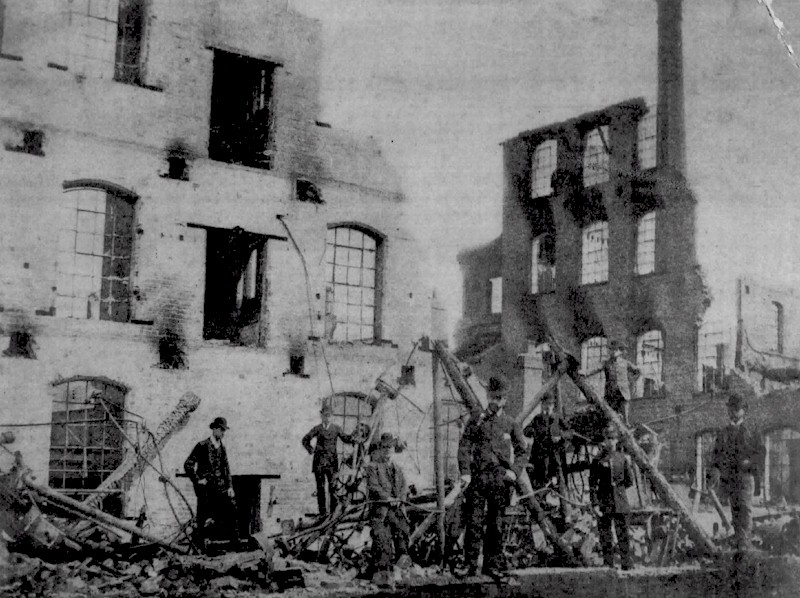

But, on 20th April 1886, just as all was in place and business was going well, tragedy struck 101. At 2.30 in the morning, the night watchman, quickly joined by two other over-night workers, discovered a fire in the building, sounded the alarm and sent for Wilkinson and his manager, Mr Jones. Quickly

realising that the available hoses were inadequate and that the fire was spreading rapidly, they called out the local fire brigade but its equipment was not up to the task, the fire now having developed rapidly. The next option was to awake the postmaster who sent a telegram to the Nottingham brigade for assistance. By now, half an hour had passed and there was another 45 minute

delay while horses were found. The brigade finally arrived at 4.30. In the meantime, the roof had fallen in and the building was past saving and the brigade assistance was limited to saving surrounding houses. The fire continued to rage all night with walls crashing down causing damage to surrounding buildings. It was a scene of utter destruction with everything on the site ruined.

Not surprisingly, the tremendous fire had attracted crowds of onlookers from all around the area, many - particularly those who worked at the factory - realising that it was a disaster for the village and, in many cases, for their own and their families' livelihood. Estimates of the number affected directly by the disaster, which appeared in the papers at the time, suggested that

some 600 had worked at the factory and there were about 400 outworkers who were directly reliant on the factory - seemingly high estimates made at the time which would have included workers from outside of Beeston. The value of the buildings lost was eventually valued at between £100,000 and £150,000 and the machines at £40,000 to £50,000. It was clearly going to be a difficult

time as, although it appears that Wilkinson was insured, at least in part, things clearly could not be restored quickly - but this would be to underestimate Frank Wilkinson who on the next day, stood defiantly in the ruins (see above right, click here or the image for more).

But, on 20th April 1886, just as all was in place and business was going well, tragedy struck 101. At 2.30 in the morning, the night watchman, quickly joined by two other over-night workers, discovered a fire in the building, sounded the alarm and sent for Wilkinson and his manager, Mr Jones. Quickly

realising that the available hoses were inadequate and that the fire was spreading rapidly, they called out the local fire brigade but its equipment was not up to the task, the fire now having developed rapidly. The next option was to awake the postmaster who sent a telegram to the Nottingham brigade for assistance. By now, half an hour had passed and there was another 45 minute

delay while horses were found. The brigade finally arrived at 4.30. In the meantime, the roof had fallen in and the building was past saving and the brigade assistance was limited to saving surrounding houses. The fire continued to rage all night with walls crashing down causing damage to surrounding buildings. It was a scene of utter destruction with everything on the site ruined.

Not surprisingly, the tremendous fire had attracted crowds of onlookers from all around the area, many - particularly those who worked at the factory - realising that it was a disaster for the village and, in many cases, for their own and their families' livelihood. Estimates of the number affected directly by the disaster, which appeared in the papers at the time, suggested that

some 600 had worked at the factory and there were about 400 outworkers who were directly reliant on the factory - seemingly high estimates made at the time which would have included workers from outside of Beeston. The value of the buildings lost was eventually valued at between £100,000 and £150,000 and the machines at £40,000 to £50,000. It was clearly going to be a difficult

time as, although it appears that Wilkinson was insured, at least in part, things clearly could not be restored quickly - but this would be to underestimate Frank Wilkinson who on the next day, stood defiantly in the ruins (see above right, click here or the image for more).Frank responded to this huge setback with his characteristic decisiveness, by transferring the majority of the curtain manufacturing to his Hall Croft factory in Chilwell - which he enlarged substantially to provide the necessary workspace - and opening another factory in Borrowash, Derbyshire while, at the same time, starting to rebuild the Beeston site. Gradually, over the next five years, curtain manufacturing returned to the Beeston site although the other sites continued, providing a degree of insurance against another disaster - it was, as we will see, just as well that this policy was followed.

The export market, particularly in America, remained an important component of Wilkinson's business. The demand for his fashionable curtains in the States was substantial and increasing - a situation that did not sit well amongst those in the States who believed that reliance on foreign imports did little for their home economy. Although it was a bitterly contested move, in October 1890, the McKinley Tariff Act became law. This increased the tariffs on a range of goods coming into the States - for lace, the tariff was increased from 40% to 60%. This was clearly another threat to Wilkinson's business but, once again, he responded decisively by paying $120,000 for a vacant mill and associated empty tenements in Tariffville, Connecticut. This was a substantial outlay, given the costs of rebuilding he had faced, not all of which had been covered by insurance. He was, however, able to use the excellent relationship with his bank - Nottingham & District Bank - which, in June 1890, granted him an overdraft facility of £30,000 against security he lodged with the bank, to be reduced by £5,000 per annum after two years. It was also agreed that, should an additional £5,000 be required for a special purpose, the bank's Board would give the application their 'most favourable consideration'.

Tariffville had taken its name, and developed its industry, based on earlier protectionist legislation - the Tariff Act of 1824 - and Wilkinson's arrival, the direct result of the latest legislation, was widely welcomed in the community. The water-powered mill had been built by the Connecticut Screw Company on the site of previous buildings built and occupied by the Tariff

Manufacturing Company and later by the Hartford Carpet Company until it was destroyed by fire in 1867. More recently, it had been used by the Hartford Silk Company. Having recently stood empty, Wilkinson's proposal to make lace curtains there was considered a new source of employment locally - and, by many, a vindication of the McKinley Act. It was generally agreed that

Wilkinson had secured a bargain (a recent photograph - shown right - seems to confirm that) - and the move may have turned a setback to his advantage, if the necessary skills could be replicated there. The American company - the Frank Wilkinson Manufacturing Company - was headed up by Frank, as President and Treasurer, with a capital of $750,000 and a team from England, brought

together to get the venture off the ground 102 :

Tariffville had taken its name, and developed its industry, based on earlier protectionist legislation - the Tariff Act of 1824 - and Wilkinson's arrival, the direct result of the latest legislation, was widely welcomed in the community. The water-powered mill had been built by the Connecticut Screw Company on the site of previous buildings built and occupied by the Tariff

Manufacturing Company and later by the Hartford Carpet Company until it was destroyed by fire in 1867. More recently, it had been used by the Hartford Silk Company. Having recently stood empty, Wilkinson's proposal to make lace curtains there was considered a new source of employment locally - and, by many, a vindication of the McKinley Act. It was generally agreed that

Wilkinson had secured a bargain (a recent photograph - shown right - seems to confirm that) - and the move may have turned a setback to his advantage, if the necessary skills could be replicated there. The American company - the Frank Wilkinson Manufacturing Company - was headed up by Frank, as President and Treasurer, with a capital of $750,000 and a team from England, brought

together to get the venture off the ground 102 :

Walter Wilkinson - who, as we have already seen, was not related to Frank, was made Vice-President. Walter had served Frank well as his export salesman and made many visits to America over the years and had undoubtedly ensured the success of Frank's Beeston products in America so far. It seems likely that it was he that put together the deal for the acquisition of the Tariffville mill and would have expected - and had probably obtained, possibly after some financial commitment - a share in its future prosperity.A few key workers also moved to America to supervise and train the workforce, many of whom were recruited locally. Those that have been identified include:

Frederic Jones - was made the assistant Treasurer and General Manager. This is the same 'Mr Jones' who, as Manager of Anglo-Scotian Mills in 1886, had raised the alarm when the fire was first discovered there. He had gone on to become manager of Frank's mill at Borrowash before this latest appointment, charged with managing the detail of getting the Tariffville mill up and running and then managing the day-to-day manufacturing process. He and his wife Henrietta - a daughter of Beeston farmer, Francis Burrows - had arrived in New York on 2 June 1891 and had taken up residence in the township associated with the mill. Then just 30 years of age, he had clearly already impressed Frank with his energy and business enterprise - qualities that were also recognised by local observers in America.

Hubert de Tracy Wilkinson - Frank's eldest son, was appointed Secretary. Hubert, then aged 21 and unmarried, had previously assisted his father in managing the mills in Beeston and Chilwell and had arrived in America on 24 August 1891.

Frank Wilkinson made a visit, no doubt to oversee progress, arriving at New York on 7 September 1891 103. His arrival so soon after that of his son is interesting but not presently explained.

Emma Marriott and her daughter Florence Edith Marriott - Emma Cutts was born in Chilwell in 1839 and married Frederick Marriott in 1860. Florence Edith was their second child, born in 1871, after which Frederick appears to have left the marital home to lead a new life in Radford and Nottingham. Emma worked at Wilkinson's Chilwell factory, eventually as an overlooker, living in the factory complex on Middle Lane, Chilwell. By the time she arrived in America, with her daughter in 1891, she has reverted to her maiden name.Meanwhile, the rebuilding of the Beeston site had been completed sufficiently enough to allow production to get underway and, in fact, the factory was often working day and night. On 29 April 1892, however, came another huge setback when it was again severely damaged by fire - exactly six years to the day since the first fire. At just after midnight, when a shift had just finished and many workers were still in the building, one of the twisthands had stayed on to prepare his machine for his colleague who would start his shift at 4am. While using a moveable gas burner to provide illumination while positioning threads, it seems he accidentally set fire to flammable material and this quickly spread, despite the man's every effort to contain the fire. Within ten minutes the fire had spread alarmingly and the workmen rushed to escape, luckily with no major casualties. The building where the fire had started was part of the newly erected buildings on the south side of the site, to the right of a gateway standing at the top of Villa Street. It was five stories high and, although the local fire brigade was quickly on the scene, they found the fire had already spread from the bottom to the top of the building and to adjoining stockrooms and Frank Wilkinson's private office. Clearly, the task was far beyond what they were able to tackle unaided and help was quickly summoned from Nottingham and other brigades in the area. They were able to fight the fire and prevent it spreading widely thanks to an adequate pressure in the local water main, helped by extra pressure supplied from the Basford pumping station. Workmen from the factory, led by George Wilkinson and assisted by local works firemen, worked assiduously to restrict the fire spreading and to remove whatever stock and machinery they could. Eventually, the building where the fire originated collapsed, destroying other buildings on the left of the gateway. But, by daybreak, the fire was under control and the substantial losses could be evaluated - they included eight curtain lace machines, four Leavers lace machines, 250 curtain taping machines and a complete lithographic and letterpress printing plant. Finished stock - mainly curtains - valued at £30,000 and cotton stock worth £10,000 was lost. In all the loss would be over £100,000 - and this time it was not fully insured 104. Tragically for Beeston and surrounding communities, between 500 and 600 employees were expected to be without employment until things were returned to normal - if they ever were.

George William Wakeling - was born in Sneinton, Nottingham in 1869 and had worked at the Beeston factory as a lace maker before moving to America in 1892. Soon after his arrival, he married Florence Edith Marriott (see above) and they were to have five children with her mother, Emma Cutts, continuing to live with the family thoughout the rest of her life.

Joseph Wright and his sons, James and Wilfred - who arrived in 1892, had each worked at the Beeston factory while living nearby at 73 Wollaton Road. Joseph (b. Beeston, 1839) and Wilfred (b. Chilwell, 1875), had both worked as lace dressers and continued in that role at the Tariffville mill. James (b. Beeston, 1868), was able to continue in his work as a lace maker.

Mary Ann Towle - who, prior to her arrival in 1891, had worked as a lace mender, living at 59 Wollaton Road, Beeston with her parents, Edmund Towle and his wife Amelia (née Eaton). She married James Wright (see above) in about 1896 and they went on to have five children.

If Frank Wilkinson had thought, up to this time, that his problems were almost behind him, they had now got very much worse. He now faced huge pressures on many fronts - his United States factory was not yet operational, his Beeston factory was once more in ruins - with all that meant in terms of loss of production - and, this time, the loss was only partly insured. All this would

almost inevitably mean his cash flow would be impacted severely and, given the investment already made, probably left him stretched financially. Happily, his relationship with his bank was, for now at least, still good, such that, in May 1892, the bank's Board agreed an additional £15,000 was to be made available against the security of his fire insurance claims. Characteristically,

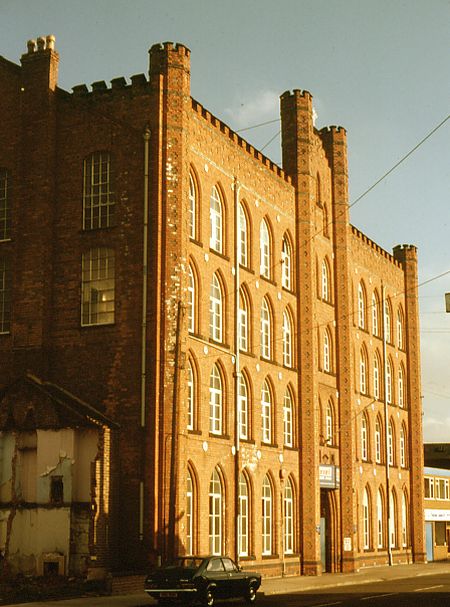

despite all of these issues, Frank responded immediately and decisively by commissioning a local architect, James Huckerby, to design a new factory building at the Beeston site to replace those that had been destroyed in the fire. His plans for the Anglo-Scotian Mill, that still stands today, were ready on 27 June 1892 - less than two months after the fire - and building got under way

straight away. The building with its imposing castellated gothic frontage onto Wollaton Road (shown left - click the image or here to see more images of the building), which some say was modeled on Thrumpton Hall, was clearly a statement of defiance and determination to overcome any and all setbacks - and the stone shields above the central entrance

dedicated this otherwise entirely practical building to its purpose - Laboremus - Let Us Do Our Work.

If Frank Wilkinson had thought, up to this time, that his problems were almost behind him, they had now got very much worse. He now faced huge pressures on many fronts - his United States factory was not yet operational, his Beeston factory was once more in ruins - with all that meant in terms of loss of production - and, this time, the loss was only partly insured. All this would

almost inevitably mean his cash flow would be impacted severely and, given the investment already made, probably left him stretched financially. Happily, his relationship with his bank was, for now at least, still good, such that, in May 1892, the bank's Board agreed an additional £15,000 was to be made available against the security of his fire insurance claims. Characteristically,

despite all of these issues, Frank responded immediately and decisively by commissioning a local architect, James Huckerby, to design a new factory building at the Beeston site to replace those that had been destroyed in the fire. His plans for the Anglo-Scotian Mill, that still stands today, were ready on 27 June 1892 - less than two months after the fire - and building got under way

straight away. The building with its imposing castellated gothic frontage onto Wollaton Road (shown left - click the image or here to see more images of the building), which some say was modeled on Thrumpton Hall, was clearly a statement of defiance and determination to overcome any and all setbacks - and the stone shields above the central entrance

dedicated this otherwise entirely practical building to its purpose - Laboremus - Let Us Do Our Work.But, it seems, his financial problems continued and were to dominate the last years of his life. By October 1892, his bank was beginning to put restrictions on his account by limiting his overdraft to £30,000 - though, in January 1893, it agreed to increase this to £40,000, against additional security. By early in 1893, during a regular sales visit to America, Walter Wilkinson found long-standing customers were beginning to withhold orders after experiencing delivery problems - understandable following the disruption of the fire but not acceptable by those who had the option to buy elsewhere. Production at the Tariffville factory could be expected to help but was not expected to be fully underway until well into 1893. Then, the workforce was expected to total 60 - sizable for a startup but small when compared with the Beeston factory - and full efficent working could not be expected for some time. This threat to Frank's key market in America - no doubt mirrored in his home market and greatly exacerbated by Walter's early death in December 1893 - added considerably to the financial problems he clearly faced. By then, his bank had clearly begun to loose confidence and took steps to safeguard its very substantial exposure to Frank - in noting that the overdraft had reached £42,848, the local manager was instructed to refuse all cheques which would increase that amount and instructed its solicitors to write to Frank accordingly. Nevertheless, Frank continued to confront these problems head-on, looking for any way to get through these set-backs to the more stable situation promised by the initiatives he had already put in place but which needed time to show benefits. What was clear however, was that, except for some relatively small advances granted against specific assets, he could no longer depend on the bank for further support.

In more prosperous times, Frank had begun to put together a portfolio of investment properties, quite apart from his substantial factory properties. These included 'The Towers', the substantial property with frontages on City Road, Nether Street and Middle Street and occupied by Walter Wilkinson's family, several adjoining building plots and out-buildings, all of which were adjacent to

Frank's own fine residence at Beeston Hall on Middle Street. There were also residential properties in Chilwell, some with associated shops, including Hall Croft Terrace and De Tracy Villas and 'a residential property on Beeston High Road' (Probably Oban House, actually on Chilwell Road). He also owned building plots in the Belle Vue Estate in Beeston and more land adjacent to the station in Attenborough. This portfolio was offered for

sale by Public Auction, held at the Durham Ox Inn at Beeston on 1st June 1894. It seems however, that these properties were held as security by the bank against his bank borrowings and most of the proceeds - probably a total of £1,470 for four of the properties - were received by the bank in July 1894. Similar small property proceeds were also repaid to the bank in the months up to February 1895. By this

time, however, the bank was becoming even more concerned and took steps to ensure that any rental payments were collected and paid directly to the bank, to insist that agreed repayments be made on time if proceedings were to avoided, that Frank's interest in the American property be assigned to the bank and that steps be taken to obtain further security against the company's fixed machinery.

Clearly, these actions provided nothing more than short-time financial fixes - they would not provide anywhere close to the level of support needed to ensure survival. One significant aspect of this is the choice of venue for the property sale - the Durham Ox - where George Wilkinson his brother, had been the landlord, as it was he who now began to take a substantial role in Frank's business affairs.

Up to this difficult time, George had a distinctly separate association with Anglo-Scotian, building and renting houses in the area for the workers - those surviving on Commercial Avenue, Wilkinson Avenue and Derby Street are a surviving legacy of this - and had prospered accordingly. Now, Frank and George began to act together to try to address the ongoing financial problems. George had visited America

in January 1894 and, in August of that year, he and Frank paid a joint visit there to assess the situation there. Also in that year they floated Anglo Scotian Company Ltd as a vehicle to take-over and refinance the Beeston business - though, perhaps because of existing encumbrances with the bank, it appears that, at this stage, the mill property itself was only leased by the new company. However, with

a share capital of £52k, £25k of which was paid-up, and a debenture issue of £52k, it was able to attract investors, many of whom were from the Newcastle-on-Tyne area. George became a Director and was to take an important and increasing part in the running of the company from that point on.

In more prosperous times, Frank had begun to put together a portfolio of investment properties, quite apart from his substantial factory properties. These included 'The Towers', the substantial property with frontages on City Road, Nether Street and Middle Street and occupied by Walter Wilkinson's family, several adjoining building plots and out-buildings, all of which were adjacent to

Frank's own fine residence at Beeston Hall on Middle Street. There were also residential properties in Chilwell, some with associated shops, including Hall Croft Terrace and De Tracy Villas and 'a residential property on Beeston High Road' (Probably Oban House, actually on Chilwell Road). He also owned building plots in the Belle Vue Estate in Beeston and more land adjacent to the station in Attenborough. This portfolio was offered for

sale by Public Auction, held at the Durham Ox Inn at Beeston on 1st June 1894. It seems however, that these properties were held as security by the bank against his bank borrowings and most of the proceeds - probably a total of £1,470 for four of the properties - were received by the bank in July 1894. Similar small property proceeds were also repaid to the bank in the months up to February 1895. By this

time, however, the bank was becoming even more concerned and took steps to ensure that any rental payments were collected and paid directly to the bank, to insist that agreed repayments be made on time if proceedings were to avoided, that Frank's interest in the American property be assigned to the bank and that steps be taken to obtain further security against the company's fixed machinery.

Clearly, these actions provided nothing more than short-time financial fixes - they would not provide anywhere close to the level of support needed to ensure survival. One significant aspect of this is the choice of venue for the property sale - the Durham Ox - where George Wilkinson his brother, had been the landlord, as it was he who now began to take a substantial role in Frank's business affairs.

Up to this difficult time, George had a distinctly separate association with Anglo-Scotian, building and renting houses in the area for the workers - those surviving on Commercial Avenue, Wilkinson Avenue and Derby Street are a surviving legacy of this - and had prospered accordingly. Now, Frank and George began to act together to try to address the ongoing financial problems. George had visited America

in January 1894 and, in August of that year, he and Frank paid a joint visit there to assess the situation there. Also in that year they floated Anglo Scotian Company Ltd as a vehicle to take-over and refinance the Beeston business - though, perhaps because of existing encumbrances with the bank, it appears that, at this stage, the mill property itself was only leased by the new company. However, with

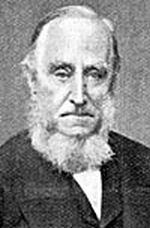

a share capital of £52k, £25k of which was paid-up, and a debenture issue of £52k, it was able to attract investors, many of whom were from the Newcastle-on-Tyne area. George became a Director and was to take an important and increasing part in the running of the company from that point on. The last few years, particularly since the time of the second fire in 1892, had been a very difficult time for Frank and it is not surprising that, it seems, his health was beginning to deteriorate - the image (above right) taken in the garden of his home at Beeston Hall at around this time, certainly seems to show this. In July 1897, while on a business visit to London, he was taken ill

and forced to return home immediately where doctors confirmed that he was seriously ill and unlikely to recover. He died on 11 August 1897, at his home in Beeston, aged only

52. Despite the fortune he had made at the height of his career, he left a relatively modest estate - £3075, later revised to £1302. But he remained a highly respected man who, despite many reverses, had done much to transform and improve the fortunes of Beeston's industrial life and the lace trade generally. His impressive memorial, stands prominently within a group of family monuments in Beeston

Cemetery (Shown left - click here or the image for more) and remains a reminder of this contribution to Beeston's growth and prosperity. The local newspaper had no doubts when it wrote that he was 'one of the best friends Beeston ever had'.

The last few years, particularly since the time of the second fire in 1892, had been a very difficult time for Frank and it is not surprising that, it seems, his health was beginning to deteriorate - the image (above right) taken in the garden of his home at Beeston Hall at around this time, certainly seems to show this. In July 1897, while on a business visit to London, he was taken ill

and forced to return home immediately where doctors confirmed that he was seriously ill and unlikely to recover. He died on 11 August 1897, at his home in Beeston, aged only

52. Despite the fortune he had made at the height of his career, he left a relatively modest estate - £3075, later revised to £1302. But he remained a highly respected man who, despite many reverses, had done much to transform and improve the fortunes of Beeston's industrial life and the lace trade generally. His impressive memorial, stands prominently within a group of family monuments in Beeston

Cemetery (Shown left - click here or the image for more) and remains a reminder of this contribution to Beeston's growth and prosperity. The local newspaper had no doubts when it wrote that he was 'one of the best friends Beeston ever had'. Frank's wife Elizabeth moved to live at 45 Dovecote Lane, Beeston and died in April 1908, aged 68. Her estate was first valued at £592 but this was later revised to £4013. The couple had five children most of whom died at a relatively young age:

Francis Wilkinson - was born in Chilwell, Notts in 1869. In 1881 he appears to be attending a boarding school on the Ropewalk in Nottingham but, after that, no trace has been found until his early death, apparently at Beeston in January 1904, aged 35. He is buried in Beeston Cemetery with his parents.For the time being, the mills in Beeston, Chilwell, Draycott and Tariffville continued to operate under George Wilkinson's management but market conditions - particularly in the increasingly competitive American market - continued to be difficult. Labour relations problems in the Beeston and Draycott mills, arising from attempts to unionise the workforce, had started by 1898 and continued as a significant issue for the rest of the life of these factories. However, by July 1899 it had been possible to repay all monies due to the bank, apparently by continuing the sell off some peripheral assets and the transfer of all the main factory assets in Britain to the operating company, Anglo Scotian Company Ltd.

Hubert de Tracy Wilkinson - was born in Chilwell, Notts in 1870. As a child, aged 10, he boarded at Hallcroft Terrace, Chilwell, Notts with Frances S E Kelsey, a school mistress, together with brothers Neville and Cecil. As a young man he worked alongside his father as a lace curtain manufacturer and, as we have seen, went to America for a short time, helping to set-up the Tariffville factory. In 1895, he married Mary Elizabeth Fazakerley, the eldest daughter of the late Edward Fazakerley, a successful Nottingham draper, and his wife Elizabeth Jane, and set-up home at Melton House, West Bridgford, Notts. A son, Kenneth de Tracy Wilkinson was born in Nottingham in 1898, although, it appears that for much of his young life he lived with his maternal great-aunt, Emma Rhoades. At the time of the 1901 census, Hubert and Mary are staying at the Imperial Hydro Hotel in Blackpool with Hubert described as a lace manufacturer. In 1916 he is recorded as living at 70 Talbot Street, Nottingham but no trace of either him or his wife has been found until Hubert's death in 1941 in Nottingham. Their son worked as a cinema operator before service with the Royal Flying Corps as a mechanic during World War 1. Kenneth married Elizabeth Reynolds in 1941 and died in 1957 in Nottingham.

Gertrude Ellen Wilkinson - their only daughter, was born in Chilwell in 1872 and died as an infant in 1874.

Neville Percival Wilkinson - was born in Chilwell, Notts in 1874. As a child, aged 8, he boarded at Hallcroft Terrace, Chilwell, Notts with Frances S E Kelsey, a school mistress, together with brothers Hubert and Cecil. As a young man he worked as an assistant to his father and, after Frank's death, he became a cotton agent. He never married, died in 1903 at Beeston, aged 29, and is buried with his parents in Beeston Cemetery.

Cecil Walter Wilkinson - was born in Chilwell, Notts in 1876 but, for some reason, he was baptised at St Leonards Church, Newark, Notts in 1888. As a child, aged 4, he boarded at Hallcroft Terrace, Chilwell, Notts with Frances S E Kelsey, a school mistress, together with brothers Hubert and Neville. In 1899 he married Clara Georgina Underwood and then worked as a commercial clerk and later as a cashier for a shawl factory, living at 211 Station Road, Beeston. He died in 1916, aged 39, by which time he and his family were living at Stafford House, Park Street, Beeston. They had one daughter, Muriel Clare Wilkinson (1902-1991) who never married. His wife died in 1958 and is buried with her husband, in Beeston Cemetery, adjacent to the large memorials to Frank and George.

During a visit to America by George in 1898, a decision was taken to discontinue production there, following which the Tariffville mill was taken over by Frederick Jones who was able to continue lace production, under the name 'Tariffville Lace Company' until 1910 when he started the Tariffville Oxygen & Chemical Company on the site. At that time, many of the lacemakers, including those who had originated from the Beeston area, moved to Chester, Delaware County, Pennsylvania where an active lace factory continued for many years.

Over the next eight years, the trading position of Anglo Scotian Company Ltd deteriorated, such that, in October 1906, a Receiver was appointed, charged with liquidating the assets for the benefit of the company's investors - mainly men of standing from the Newcastle-on-Tyne area - and its creditors - happily, relatively small in value. It was likely to be a big task - as well as the Beeston factory, there were 35 lace machines and a large stock of yarn and finished items that, it was hoped, would go some way to meeting the company's liabilities of about £100k.

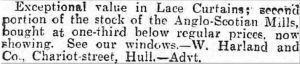

When early attempts to sell the company as a going concern failed, these assets were sold to those making the best offer and, by the following year, curtain stock at bargain prices was being offered - as the advert (right) from May 1907 from the Hull Daily Mail shows. The mill site proved to be more difficult to sell and the liquidators added improvements - including an additional steam engine

- to make it more attractive to a purchaser. Eventually, the whole complex, covering 8120 square yards, complete with existing tenants, was sold to Arthur Pollard, the latest to run the family lace business at nearby Swiss Mills. At £8,500, it was a considerable bargain as the existing tenants were paying a total of nearly £1800 per annum in rent and there was potential for another £1000 from the

When early attempts to sell the company as a going concern failed, these assets were sold to those making the best offer and, by the following year, curtain stock at bargain prices was being offered - as the advert (right) from May 1907 from the Hull Daily Mail shows. The mill site proved to be more difficult to sell and the liquidators added improvements - including an additional steam engine

- to make it more attractive to a purchaser. Eventually, the whole complex, covering 8120 square yards, complete with existing tenants, was sold to Arthur Pollard, the latest to run the family lace business at nearby Swiss Mills. At £8,500, it was a considerable bargain as the existing tenants were paying a total of nearly £1800 per annum in rent and there was potential for another £1000 from the

vacant rooms. After some additional improvements - notably, conversion to electrical power - Pollard was able to operate it successfully at least for the time being, in much the same way as Swiss Mill - mostly with lace making tenants but with a few of his own machines. The company nameplate from that era (shown left) survived on the gate at the top of Villa Street until into the 1980s although, by

then, the site as a whole had seen further significant changes in ownership. In about 1923, one of the tenants, the curtain manufacturer A & F H Parkes, purchased the front part of the factory (which included the striking facade on Wollaton Road) and it became known locally as 'Parkes Factory' - a name that will be remembered by many and still used today by some in Beeston. Over the years, the number

of lace tenants gradually declined such that, by the time the Pollard family sold the remainder of the complex in the 1960s, essentially all had left and there was then a range of tenants in a variety of other trades. By the 1960s, the main part of the factory was occupied by Ariel Pressings, manufacturing small electrical components, who continued there, including their successors, up to 2003. In 2004,

yet another spectacular fire destroyed part of the complex. The site is now Grade II listed, and has been acquired and tastefully converted to residential use by the local development company, Gilbert & Hall.

vacant rooms. After some additional improvements - notably, conversion to electrical power - Pollard was able to operate it successfully at least for the time being, in much the same way as Swiss Mill - mostly with lace making tenants but with a few of his own machines. The company nameplate from that era (shown left) survived on the gate at the top of Villa Street until into the 1980s although, by